A client recently asked me a favour and, out of compassion and curiosity, I agreed.

The woman’s mother had passed away not that long ago and she was keen to have a design on her body that served as a memorial. Memorial tattoos are not uncommon – there are few instances that lay the human mind more open to issues of symbolism and memory than death – particularly when a loved one is involved. Most of my work on skin is a result of customising or creating something entirely new for clients and this woman was no exception. Her mother habitually wore a piece of silver jewelry in the design of a heart enclosing another smaller heart at an angle. Keen to avoid heavy black lines and to describe the image through shading alone, I drew this.

The design was accepted and the client asked me a favour; would I be willing to include a trace of her mother’s ashes into the ink?

This was a novel request for me. As I thought about it, it occurred that I really didn’t want a reputation as ‘the guy who does that’. On the other hand, I was curious as to the practicalities of the process. I have a tattooist friend who once sprinkled some of his deceased dog’s ashes into some black ink and then tattooed a small balloon on himself (the dog loved chasing balloons). My client seemed intelligent and level-headed so, like a lot of custom-design choices, she was the right kind of person to work with. I know that sounds vague but when you work towards a custom piece, good communication and a general sense of mutual ideas pointing in the right direction invokes an intuitive feeling that all will go well. On the understanding that this was a one-shot favour, was absolutely not a service that the shop provided as a matter of course, and was best kept relatively discreet, I agreed. I asked her to drop by a small amount of her mother’s ashes two weeks in advance of the appointment.

Initially, after reading a few bizarre and unconvincing articles involving blenders and vodka, I wasn’t finding many sets of instructions on the process that I trusted. A reason I wanted to do this (and to write about it) concerned the difficulty of getting ash into skin, possible health implications, avoiding healing problems or excessive skin irritation, and, not least of all, respecting human remains throughout the process. I knew anecdotally that the presence of coarse particles would clog the needle formations of a large curved shader, particularly as softer shading effects involve turning the machine down to a purr. Additionally, coarse particles will sink to the bottom of the ink cap so they would likely be either drawn up at once into the tip, blunt the needle, or not be taken up at all. Ash in liquid suspension was the ideal so I set about filtering the sample I was given.

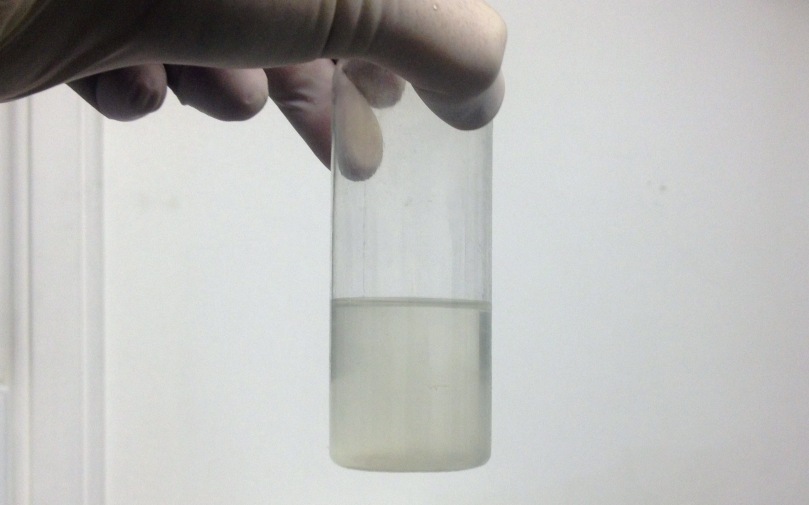

Unsurprisingly, isopropyl alcohol turned out to be an effective solvent. With a great deal of stirring with a wooden tongue depressor, the more powdery material dissolved, leaving a very coarse ‘sand’ that instantly sank in the mix. I believe this heavier material is likely oxidised bone, crushed and pulverised in a machine following the actual cremation.

The mix was passed through a filter paper into a small container. By far, the majority of the mixture didn’t make it through. The isopropyl was cloudy with tiny particulate matter too small for the naked eye. The remaining ash was returned to the original container and placed in front of a mild heat source to evaporate off the remaining solvent.

After some time, the remaining mixture settled to produce a very fine sediment, not dissimilar to how a bottle of tattoo ink settles over time. I placed a ‘lid’ of folded tissue towel over the bottle and tied a rubber band around the top to prevent dust entering and to allow the isopropyl to evaporate.

The fine powder deposit constitutes the only ash to be introduced into the grey-wash. Despite the sterilising properties of a crematorium operating at enormous temperatures, I made a tiny package for the autoclave so that the ashes could be sterilised to studio standard.

So that’s it – the powder was delicately stirred into one of the dilutions and it was simply business as usual. This is the finished result, obviously, things will look more settled once the skin has healed.

Choosing to alter one’s skin is no small decision. For the tattooist, choosing to be responsible for that process should be no less of a concern. When thinking about introducing a foreign substance into ink I obviously had to research health implications. I am no medical professional but, for those concerned, I will summarise the issues as I saw them.

Particle size

The filtration and refining of the ashes ensures that no excessively large or coarse particles would be introduced to the skin. This minimises the likelihood of excessively inflamed or irritated skin throughout the healing process, thus reducing healing time and preserving the integrity of the tattoo.

Toxicity

The chemical components of crematorium ash can be researched online. In short, the constituents are dominantly oxides and salts. As combusted remains, these are thoroughly reacted and relatively inert substances – little more than ‘dirt’. Despite the apparently harmless nature of ash, it still makes sense to use a very small quantity.

Chemical reaction with ink

The grey wash is essentially carbon in solution. As such, it is not likely to react with the ash in any visible or harmful manner.

Risk of infection

The crematorium is a far more effective steriliser than the average tattoo shop autoclave (also used by dentists, cosmeticians, etc). Microbial or viral traces are totally eliminated and not even prions or other protein packages would endure the flames. I chose to further autoclave the ashes I prepared on the remote chance that my process of filtration had contaminated the sample. I can see no risk of passing infections from the human remains to the recipient. I assess that following my procedure raises no additional risk of infection from any tattoo process.

Efficacy of pigmentation

Provided that the client understands there is an outside possibility that there might be minor skin irritation during healing, and that this may effect the healed result, the visual product should be no different from any other tattoo. The ash is not a pigment or colouring agent and will not be visible in the skin.

Aftercare

A sensible routine is required for all tattoo aftercare and the presence of ash makes no difference. I recommend to all clients that they use small quantities of Bepanthen as a sterile barrier (vegan alternatives are available), that they avoid soaking in water, excess friction or sweat, and that they do not pick or scratch at the healing surface. Healing time varies across individuals but two weeks is an average healing duration.

Psychological

The client has their own reasons for requesting the inclusion of ash into the ink. The simple fact is that they are bereaved and that this is likely an emotionally raw experience to endure as well as a physically painful one. Whether experiencing catharsis or closure, the client is having a hard time and respecting the use of human remains seems essential.

I hope anyone wanting to research this topic found it useful. Let me know if you have any feedback.

Disclaimer

I am not a medical professional. I chose to publish this article (with the permission of my client) on the grounds that I carefully approached this subject with respect and diligence. I accept no responsibility for the results of this method or those who follow it.